Introduction

Free will is thought to be a key characteristic of human nature, crucial in regulating our social life. However, what at first seems to be an evident condition is in fact a very debated concept in philosophy. Free will is very difficult to define and to justify: defining it is indeed a key issue in determining if it exists or not. The current best definition of it, used in modern cognitive science (Lavazza, 2016) and philosophy is the following: free will is the “ability to do otherwise”, to have “control over possible choices” and to take “rationally motivated” decisions. In this essay I am going to examine some of the prominent positions regarding free will, to finally see how cognitive science is now re-shaping the debate in favour of a more scientific understanding of the question.

A philosophical perspective

There are hundreds of different questions regarding free will, from who actually is the alleged possessor of the will to the relationship between freedom and the laws of nature. The latter is perhaps the most debated through the history of philosophy.

Every philosophical discourse on free will is, anyway, purely metaphysical. The first philosopher to recognize this was Immanuel Kant. In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant illustrates four so-called antinomies that arise when pure reason tries to establish truths about transcendental ideas. The proposition and the contradiction of an antinomous statement can both be logically well founded, revealing a contradiction in the laws of reason. The third of Kant’s antinomies regards precisely the relationship between freedom and the laws of nature: it can be both argued that freedom exists and that the laws of nature are not enough to fully explain the universe, and that freedom does not exist and the laws of nature can explain everything that happens. Centuries after the formulation of this antinomy, we are far from a solution to the problem.

The problem of compatibility between free will and determinism sees many solutions among philosophers. Determinism is the thesis that given the state of the world at any instant there is always exactly one physically possible future. It is important to note that determinism cannot be entirely deducted from the principle of universal causation – that is, the thesis that every event has a prior cause. This implies that ruling out determinism does not make the universe completely chaotic or impossible for science to describe. This distinction is critical when countering the “compatibility problem”. Determinism and free will are not compatible, whereas free will and causality might be (for an exhaustive philosophical justification of incompatibilism see van Inwagen, 1983). Incompatibilism avoids metaphysical dualism, but it implies that we should either reject free will or determinism.

Baruch Spinoza is perhaps the philosopher that better depicts a fully deterministic world, in which the concept of human freedom acquires a completely different meaning. To Spinoza a thing is free “if it exists and acts from the necessity of its own nature alone”: he places true freedom not in unconstrained choice, but in “free necessity”: a free subject needs to be causa sui. It follows that only God (or, which to Spinoza is the same thing, nature) is free: freedom is only a characteristic of the whole system. As regards humans and “other created things, which are all determined by external causes to exist and to produce an effect in a certain determinate way” (Spinoza, letter 63, 25 July 1675), their freedom is purely illusory. It resembles that of a stone, that, thrown in the air by an external cause, “while continuing in motion, should be capable of thinking and knowing, that it is endeavouring, as far as it can, to continue to move. Such a stone, being conscious merely of its own endeavour and not at all indifferent, would believe itself to be completely free, and would think that it continued in motion solely because of its own wish. This is that human freedom, which all boast that they possess, and which consists solely in the fact, that men are conscious of their own desire, but are ignorant of the causes whereby that desire has been determined.” (ibid.) Humans can only achieve true freedom by being aware of the causes behind their desires and controlling them, by acting consciously following necessity. Free will is merely a product of our consciousness and our ignorance.

At first, it would seem that such a conception of freedom erases the existence of moral responsibility completely. It is fascinating in this sense that Spinoza’s main work is in fact an “Ethics”.

On the other hand, leaving the work of Spinoza, science is recently starting to show that determinism might not be so reasonable to accept, as quantum mechanics and chaos theories are beginning to show. Thus, there might still be a chance for free will to exist in his commonsensical conception. However, the early findings of cognitive science seemed to point towards a definitive rejection of freedom.

Cognitive science tackles the question

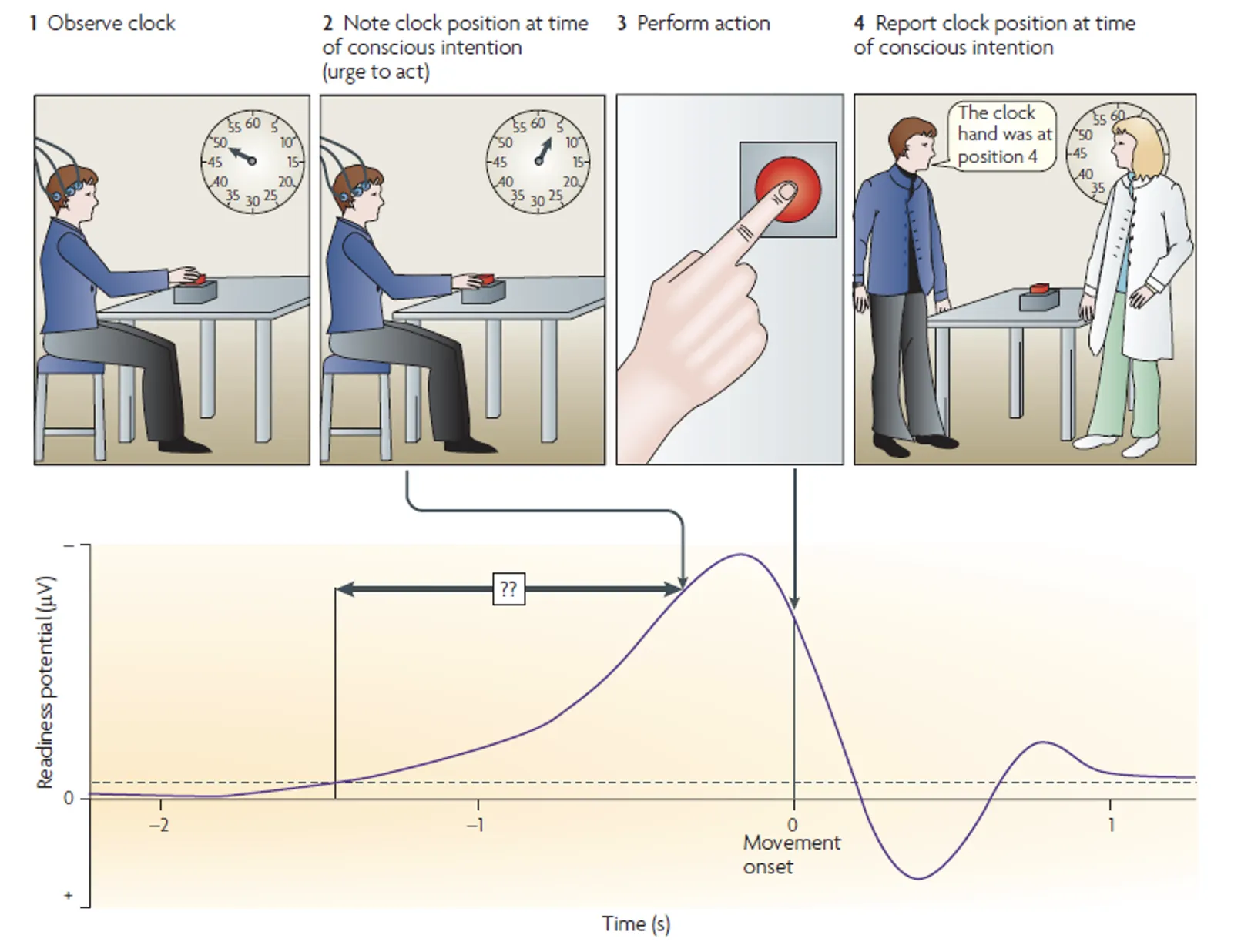

The first investigations of possible brain correlates of free will were led by Libet et al. in 1983. In Libet’s classic experiment participants had to move their right wrist and report, using a clock they had in front of them, the exact moment they decided to do so. During the task, the electrical activity of the participant’s brain was recorded. It was found that a readiness potential (RP) for motor actions builds up in the supplementary motor area (SMA) of the brain about 350 ms before the subject becomes aware of the intention to act (see Figure 1 for a schematized explanation of the experiment). It seemed like the brain “decided to act” well before the subject was conscious of it.

Since their publication, Libet’s results have been generalized and reproduced multiple times (Haggard and Eimer,1999). In a recent fMRI study (Soon et al., 2008) researchers were able to predict subjects’ simple motor decisions by statistically analysing neural activation patterns in the SMA and frontopolar cortex. A prediction of the subject choice – pressing a button with either the left or the right index finger – was made up to 7 s before the subject himself was aware of the decision.

Such findings all seem to suggest that free will is an illusion. If consciousness has to play a role over free initiated acts, then these experiments show exactly the opposite.

Different interpretations of Libet’s findings

Libet-like experiments have been extensively criticized. First of all, through the years, different explanations of the nature of the readiness potential have arisen. It may not at all reflect only action build-up, as it has also been observed in situations with an absence of movement (Alexander et al., 2016). The RP could also be interpreted in relation to stochastic neural activity (Schurger et al., 2012): movement does not significantly modulate the RP background amplitude. It is also interesting to note that the RP is only indicative of the when and whether an action is performed, but has no information regarding what task is performed. It is a process that occurs very late in the causal chain of performing an action, and thus may not be a good point of focus for the resolution of the free will problem.

Secondarily, the theoretical framework of the experiment has been itself a source of many criticisms. The action in most of the experiments is only freely initiated, and not decided. Moreover, is freely choosing when to do an instructed act in a constrained environment really acting freely?

Lastly, the autonomy of the subject relative to the unconscious onset of action may be preserved by the so-called veto power. Libet himself thought that between the elicitation of the RP and the actual execution of the action there was time for the prefrontal areas to inhibit movement. Recent studies (Schultze-Kraft et al., 2016), confirmed that people could inhibit upcoming movements up to 200 ms before movement initiation. The conscious veto offers a fertile ground to talk about more modern aspects of the free will debate in cognitive science. They regard mechanisms of control and decision-making in the brain.

Re-framing the argument

As we have seen, from a philosophical point of view it is not possible for the subject to be causa sui, and from a scientific point of view, it is not possible for consciousness to be the source of voluntary actions. Cognitive scientists try to solve the problem by treating voluntary action in terms of decision-making. Every action is in fact not a linear process with a mysterious start, but the outcome of a multiplicity of causal elements at work in and outside the brain. These elements include stochastic events, brain activity and the history of the subject’s previous choices (which is in turn in part stochastic and in part causally justified): taken together, these shape decision-making and are modified in turn by decision making in a feedback loop. Voluntary action is nothing but intelligent interaction between the animal and the environment, influenced by his current and historical context; it is not uncaused initiation of action (Haggard, 2008). The brain circuitry supporting volition includes subcortical loops in the basal ganglia which interact then with the prefrontal areas, the preSMA, the SMA and finally the motor areas. Each of these areas has a specific function in the decisional process, from regulating the reward systems (basal ganglia) to controlling and adapting the actions to the right situation (prefrontal cortex and preSMA in particular). Apart from its neural correlates, decision making has also some compelling computational models (Dayan, 2008), that can account for different value systems and control mechanisms.

And is precisely the concept of control to have a prominent position in the current debate on free-will. Patricia Churchland (2006) proposes a working concept of responsibility based on the idea of self-control, and how it is wired in the brain not only of humans but also of other animals. As a society, we need to hold people responsible for their actions, whether metaphysical free-will exists or not. Self-control is mediated by pathways in the prefrontal cortex and preSMA, can come in many degrees and can also be impaired or diminished in different cases. A person whose self-control is impaired cannot correctly exercise “free will”, and cannot be morally responsible for certain actions: an example could be a patient with a unilateral preSMA lesion resulting in the “anarchic hand” syndrome: he is no more responsible for the actions performed by the afflicted hand than another person is.

Conclusion

As we have seen, modern cognitive science has shifted the focus of the free-will debate to more tangible and scientific measurable variables, such as the intactness of self-control and decision-making systems in the brain. But is this really solving the problem?

It seems like after many decades of scientific research we have come to the same conclusion many philosophers such as Spinoza had already drawn. Free will does not exist in his common-sense conception of consciously initiating voluntary acts, and in order for it to be saved as a concept, it needs to acquire an entirely different meaning, such as the definition presented at the beginning. We have already seen how eliminating the role of “consciously initiated acts” from the free will debate might not at all be a problem for moral responsibility if we adopt working concepts such as the one Churchland proposes. Should we then abandon the idea of free will in favour of more clearly defined concepts? Maybe this might be the only way of solving Kant’s antinomy, which, after all, was a metaphysical problem. Or is it?

References

Alexander, P. et al. (2016) ‘Readiness potentials driven by non-motoric processes’, Consciousness and Cognition, 39, pp. 38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2015.11.011.

Churchland, P. (2006) ‘Do we have free will?’, New Scientist, 192(2578), pp. 42–45. doi: 10.1016/S0262-4079(06)61107-X.

Dayan, P. (2008) ‘The Role of Value Systems in Decision Making’. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/9780262195805.003.0003.

Haggard, P. (2008) ‘Human volition: towards a neuroscience of will’, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(12), pp. 934–946. doi: 10.1038/nrn2497.

Haggard, P. and Eimer, M. (1999) ‘On the relation between brain potentials and the awareness of voluntary movements’, Experimental Brain Research, 126(1), pp. 128–133.

Kant, I. et al. (1998) Critique of pure reason. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press (The Cambridge edition of the works of Immanuel Kant).

Lavazza, A. (2016) ‘Free Will and Neuroscience: From Explaining Freedom Away to New Ways of Operationalizing and Measuring It’, Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00262.

Libet, B. et al. (1983) ‘Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential). The unconscious initiation of a freely voluntary act’, Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 106 (Pt 3), pp. 623–642.

Schultze-Kraft, M. et al. (2016) ‘The point of no return in vetoing self-initiated movements’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(4), pp. 1080–1085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513569112.

Schurger, A., Sitt, J. D. and Dehaene, S. (2012) ‘An accumulator model for spontaneous neural activity prior to self-initiated movement’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(42), pp. E2904–E2913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210467109.

Soon, C. S. et al. (2008) ‘Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain’, Nature Neuroscience, 11(5), pp. 543–545. doi: 10.1038/nn.2112.

Spinoza, B. de, Curley, E. M. and Spinoza, B. de (1994) A Spinoza reader: the Ethics and other works. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Van Inwagen, P. (1983) An essay on free will. Oxford [Oxfordshire] : New York: Clarendon Press ; Oxford University Press.